Thom Hartmann: Hello, I'm Thom Hartmann in Washington, D.C. and tonight we talk to one man for the hour, climate scientist Michael Mann in a special climate change edition of The Big Picture.

You need to know this: 100% of all credible climate scientists agree that global warming is real and that it's man-made. Some even think it's going to be a lot more destructive than we originally thought. So why is it taking so long to put together a comprehensive plan to stop climate change?

For the next hour we're going to delve into the details of global warming with world-renowned climate scientist Dr. Michael Mann. We'll go over the basics of what global warming is, what's causing it, we'll talk about some of the worse case scenarios involving runaway climate change, take down the denial myths pumped out by the fossil fuel industry and put forward solutions to the greatest environmental crisis our planet has seen perhaps in the history of the human race.

Joining me now from State College, Pennsylvania, is Dr. Michael Mann, distinguished professor of meteorology and director of the Earth System Science Center at Penn State University, and the author of the book The Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars: Dispatches from the Front Lines. Dr. Michael Mann, welcome back. It's great to have you with us.

Michael Mann: Thanks, Thom, it's great to be with you.

Thom Hartmann: Let's start off with the basics. Global warming is something most people have heard about, but probably even fewer actually understand. So, can you walk us through it in layman's language? What is global warming? Why is it happening? And perhaps most importantly, how do we know that it's happening?

Michael Mann: Sure. So, despite the fact that climate change, global warming, is sometimes characterized as new and controversial science, it's actually basic physics and chemistry that goes back nearly 2 centuries. And it has to do with the simple fact that certain gases in our atmosphere, like carbon dioxide, have this heat trapping ability - they keep some of the heat that comes in from the sun, warms the planet, some of the heat produced by the planet response is trapped within the atmosphere and so it warms up the planet to a higher temperature than it otherwise would be. In fact, if it were not for the greenhouse effect, we would live, or in fact we probably wouldn't be alive; Earth would be a frozen planet. So the greenhouse effect in fact is responsible for the fact that the Earth is a habitable planet. Of course, too much of a good thing can be a bad thing and in the case of fossil fuel burning and other human activities we are increasing the temperature of the Earth's surface by raising the greenhouse effect to an extent that we are already seeing some very damaging impacts.

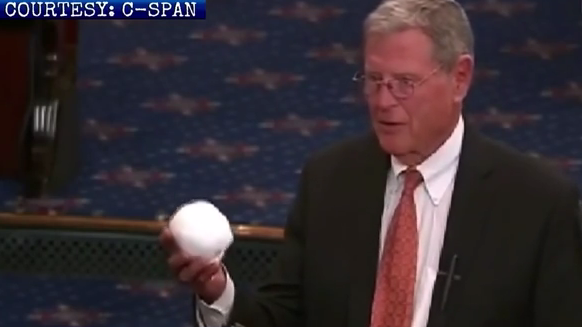

Thom Hartmann: One of the biggest mistakes that people make when it comes to global warming or climate change is confusing weather with climate. Senator Jim Inhofe gave us a great example earlier this year. Check this out:

Sen. James Inhofe (R-Okla.): In case we had forgotten, because we keep hearing that 2014 has been the warmest year on record, I ask the chair, do you know what this is? It’s a snowball, just from outside here. So it’s very, very cold out, very unseasonal. So here, Mr. President, catch this.

Thom Hartmann: So, Dr. Mann, a lot of people are persuaded by that kind of stuff, it got heavy coverage on Fox so-called News. So walk us through this, what's the difference between climate and weather, and why could we have such a cold winter when the planet is warming so rapidly, at least the winter on the East Coast here?

Michael Mann: Right, so James Inhofe would do well to read some Mark Twain because Mark Twain explained this more than a century ago when he said that climate is what you expect, weather is what you get. Climate is the statistics of the weather. We can't predict what the exact weather will be here in State college two weeks from now, three weeks from now, let alone several years from now, but we can predict that six months from now it'll be colder and a year from now it will then be warmer again. That's seasonality. That's the seasonal cycle, and that's climate.

But climate is more than just the seasonal changes in temperature and rainfall patterns, it's the longer term changes due to things like El Niño events, due to natural factors like volcanoes and small but measurable changes in solar output, and of course due to human impacts, due to the increase in the concentration of these greenhouse gases from fossil fuel burning and other human activities..

So, what we know is that heat waves are becoming more common and will become more common and they'll become more intense. Hurricanes will become stronger. Sea level will continue to rise. We will see longer and more intense droughts over large parts of North America and other continents, and so on. Those are changes in the average statistics of the weather, and we know how they are going to change with some degree of confidence.

Thom Hartmann: You're the creator of the ...

Michael Mann: Now...

Thom Hartmann: Oh, I'm sorry, go ahead...

Michael Mann: Oh, I was just going to say, so it is true that we are seeing extreme weather events that we think are being impacted by climate change and sometimes the connection is a bit non-intuitive. For example, the very cold winters we've had in some parts of the eastern U.S. in recent years are part of an unusual change in the track of the jet stream. And that same track of the jet stream that's been bringing some unusually cold air plunging southward into the eastern U.S. has instead been bringing all the storms and the moisture with them up into Alaska, away from California, and that's part of why we are seeing record drought in California right now.

So, there are changes, for example, in the pattern of the jet stream that are giving us more extreme weather events of various sorts that we also think are related to climate change. We think that that change in the jet stream may be a result of the melting of sea ice up in the Arctic which actually changes the heating of the atmosphere, it changes the pattern of the jet stream. So there are various ways in which extreme weather events that are becoming more frequent, are probably as well tied to human-caused climate change.

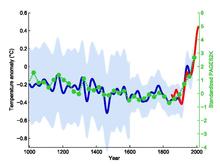

Thom Hartmann: You're the creator of the famous hockey stick graph. What does that graph tell us about global warming and climate change?

Michael Mann: Well, it sort of reinforces what we already know. We know that the warming of the Earth is unusual; the warming that we've seen in recent decades, over the last century, and we know it's because of increasing greenhouse gas concentrations from human activity, from fossil fuel burning. What we didn't know for a long time was just how unusual is that sort of warming in a longer term context because we only have about a century or so of widespread thermometer measurements around the globe. So from the instrumental data alone we can only document how temperatures over the globe or temperatures in the northern hemisphere have changed over the past century or so. And that doesn't tell us how common it might be to see a warming trend of the magnitude we've seen over centennial time scales farther back into the past.

And so what we did back in the late 1990s was use information from what we call proxy records. These are indirect thermometers. They're things like tree rings and corals and ice cores and sediments, various physical or chemical measurements from our environment that actually tell us something about past climate conditions. And we use those data to reconstruct how the temperature of the northern hemisphere had changed over the past thousand years.

And what we found was indeed that the recent warming has no precedent as far back as we were able to go. Now, since then, many other researchers using different methods, different types of data have independently sought to reconstruct climate back in time and we now know that the recent warming, the warming of the past few decades is likely without precedent even farther back. At least 1300 years, perhaps tens of thousands of years. Some of the work that has been done over the past few years suggests at least tentatively that we are now at a level of warming and a rate of warming that we cannot see going back into the last ice age and beyond.

Thom Hartmann: Wow. Outside of the pure data, what's the major evidence of global warming that we can see around us right now?

Michael Mann: Well, you know, we can see that ice is disappearing around the world, and it's doing so at an alarming rate. Mount Kilimanjaro, this magnificent ice-capped mountain at the equator, eastern equatorial Africa, immortalized by Ernest Hemingway's "Snows of Kilimanjaro", well those snows are disappearing before our eyes. We are seeing the loss of that ice cap and we know it's been around for more than 10,000 years.

We are seeing ice retreat around the globe. Sea ice, land ice, mountain glaciers, and the ice sheets; the Greenland ice sheets and the West Antarctic ice sheet. We are seeing rates of retreat of ice that have no precedent in tens of thousands of years. And that's really the cause for concern. It isn't just how warm we've made the planet, but the rate at which we are warming the planet, and the rate at which ice is disappearing, at which climate zones are migrating, climate change is occurring at a rate that is faster than we have reason to believe we or other living things can adapt to. It's really that rate, that dramatic rate of warming and of change in our climate. When human civilization developed over a period of relative climate stability and we depend on that climate stability. In fact, it's leveraged now by a population of more than 7 billion people and so we are highly dependent on the stability of our environment to support that very large population. And we're changing things faster than nature has changed them in the past. That's the cause for concern.

Thom Hartmann: How is global warming affecting or interacting with some of the major environmental crises we're seeing right now? California's drought, there are people suggesting that the whole Arab Spring phenomenon was the consequence of drought killing off the wheat crops in the Middle East, that sort of thing, in the minute that we have left in this block.

Michael Mann: Yeah, absolutely. One of the concerns here is that climate is what national security experts call a threat multiplier. It takes existing tensions over land, over water, over food and it exacerbates those tensions because it reduces access to food, land and water. And so it is sort of a perfect storm of consequences coming together to create potentially a major national security threat especially in regions like the Middle East which are already a tinder box. It's like adding fuel to the flame, climate change.

Thom Hartmann: Yeah. It's remarkable. More with Dr,. Michael Mann right after the break.

Thom Hartmann: Welcome back. I'm talking about global warming with one of the world's leading climate scientists, Dr. Michael Mann, distinguished professor of meteorology and director of the Earth System Science Center at Penn State University, and author of the book The Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars: Dispatches from the Front Lines.

Dr. Mann, one of the things I hear from right wingers all the time is that there actually hasn't been any warming over the last decade and a half. is that true? And if not, where does this whole "pause in the warming" myth come from?

Michael Mann: Yes, one of what we call the climate change denial zombies. It doesn't matter how many times that myth, that talking point is disproven, is discredited, it just keeps on coming back. And there's absolutely no truth to the statement whatsoever. Every legitimate measurement of the temperature of the Earth, whether from satellites, whether from surface observations, thermometers, tells us that the globe continues to warm at a rate of about a degree Celsius per century. It's continuing on that trajectory as we expect it to. 2014 was the warmest year on record. 2015 is shaping up to be an even warmer year. 2015 is so far the warmest first half year that we've ever seen. So global warming continues apace. The globe continues to warm, ice continues to melt at an alarming level, but you continue to hear these specious claims that the globe isn't warming.

It in part comes from work that was done more than a decade ago which has now been entirely discredited. There was one group, two scientists, who are actually climate change contrarians and they had claimed for the longest time that the satellite data showed that the Earth wasn't warming when other scientists were able to get hold of that data, what they found was that those scientists had made what we call a sign error. What that means is that where there was supposed to be a plus in their algorithm, there was a minus sign. They were literally taking a warming trend and turning it into a cooling trend. And that work has now been exposed as invalid. Other scientists have gone in and done it the right way and the satellites show that the globe continues to warm at the rate we know it's warming from other lines of evidence.

Another example is what climate change contrarians will do, there's a sleight of hand in what they will often do: they will start with a very warm year like 1998. 1998 was the warmest year on record at that point, It was boosted by a big El Niño event; the warmest year that we had ever seen at that point. Now, of course, we have seen even warmer years. And what they'll do is they'll start their trend line with that very high 1998 value and then what they'll do is draw a trend line to subsequent years. Well, of course those subsequent years are cooler because you had just set a record in 1998. And so if you start playing those games, it's easy to distort what's actually happening through faulty statistics. And if you do it right, if you do it objectively, you stand back, you estimate the temperatures, the temperature trends correctly, what they show is that the globe continues to warm at the rate that climate models tell us it ought to be warming as we continue to pump these greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

So, no matter how many times these talking points, these zombie climate change denier myths are struck down or discredited or refuted, they just keep coming back because there's a large audience for that sort of misinformation and disinformation, and often there isn't somebody there to correct the record when these specious claims are made.

Thom Hartmann: Tragically. The traditional benchmark for acceptable levels of global warming has been two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. Why that number, two degrees Celsius, and what happens after two degrees Celsius, and how close are we to reaching that benchmark?

Michael Mann: Yeah, well that's a great question. We often hold out that number two degrees Celsius, that's three and a half degrees Fahrenheit relative to pre-industrial times as that level of dangerous interference with the climate system. We've already warmed one degree Celsius. We've probably got at least another half a degree Celsius in the pipeline, just from the greenhouse gases we've put into the atmosphere so far. So that gives us a very small cushion, very little wiggle room. There's only about a half a degree Celsius left to play with before we exceed that two degrees Celsius warming threshold. And if we continue with business as usual - fossil fuel burning for another decade - then we will commit to passing that threshold. That's why it's so urgent to reduce our carbon emissions now.

Now, there is in reality no one fixed number, two degree Celsius. A lot of bad things we think happen if we warm the planet two degrees Celsius. But even worse things happen if we warm the planet three degrees Celsius, and so on. So rather than this being a cliff that we fall off at two degrees Celsius it's much more like a steadily sloping down hill and the further we go down that hill the more we imperil ourselves. But if we miss that two degrees Celsius exit, if we're unable to reduce our emissions rapidly enough to avoid that two degrees Celsius warming limit, it doesn't mean we give up, Thom. What it means is we take the next exit ramp. We take the 2.2 degree Celsius warming exit ramp. The less warming, the less likely it is that we will see dangerous and potentially irreversible changes in our climate.

But, you know, if you talk to people in Tuvalu, if you talk to people who inhabit low-lying island nations, if you talk to people who live in Miami Beach, if you talk to people who live in California, they'll tell you that dangerous climate change isn't some far-off thing that might happen in the future, it's happening now.

Thom Hartmann: Former NASA scientist James Hansen is saying that two degrees, that that two degree threshold is actually too high, that it allows for devastating multi meter high sea level rises. What do you think? And if Dr. Hansen is correct, what kind of consequences does that have for this whole process of how we're trying to stop global warming?

Michael Mann: well, you know, we dismiss what James Hansen has to say at our peril. He's often been criticized for making pronouncements like that but he has also shown a penchant for being remarkably prescient. Back in 1981 he published a groundbreaking paper that literally predicted how much warming we would see in the decades ahead with a remarkable degree of accuracy. Back in 1989

he spoke on the U.S. Senate floor, for the first a climate scientist said, you know, human caused climate change is here, we are seeing it. And he was right then. So he has this remarkable history of making prescient predictions about the future and what he's saying now should not be dismissed.

He is arguing for the possibility that we will see quite a bit more sea level rise, more melting from the ice sheets - the West Antarctic ice sheet, the Greenland ice sheet - than climate models currently predict. More rapid sea level rise over the next 50 years than the climate models predict. And in fact, if you look at the climate projections, if you look at the predictions we made about sea level rise, the predictions we've made about arctic sea ice and how fast it would decline, in many respects the climate is changing faster and with greater magnitude than we predicted just years ago.

And so it may very well be true that Hansen is right and the climate models that we are using right now upon which to base policy are actually underestimating the rate at which we will see rise in sea level and a whole array of other negative climate impacts. It really stresses the fact, what we call the precautionary principle. We are tampering with the only planet we know of in the universe that supports life. There is no planet B. If we screw this one up, there is no recourse. And so we should be extremely cautious in tinkering with a system we don't understand perfectly because the changes may end up being far worse than we predict today.

Thom Hartmann: Some scientists like Dr. Guy McPherson have an even bleaker view of global warming, say that it's making such drastic changes to the atmosphere that it's pushing us outside the habitable zone and that we might have already passed some irreversible tipping points. Here's a quick clip of Guy McPherson on that:

Guy McPherson: We're so close to the sun, we're so close to the inner edge of the habitable zone for life on Earth that even a minor change in atmospheric composition could push us out of the habitable zone. Well, we haven't made minor changes in the atmospheric chemistry of the Earth; we've made major changes in the atmospheric chemistry of the Earth.

Thom Hartmann: So, what do you think about that? Could global warming lead to the end of much or all life, at least all large and complex life on Earth?

Michael Mann: Well, I don't know about that. There's quite a bit of uncertainty about the projections and we always have to keep in mind worse case scenarios because, as I said before, the climate model projections have a history of actually having been too conservative. The scientific community, in a sense, has a history of having been too conservative. So, we shouldn't dismiss out of hand voices like James Hansen or even McPherson who are telling us that it could be worse than what the climate models are currently telling us.

That having been said, based on my assessment of the science, my objective assessment of what the science actually tells us right now, I don't think we've passed a tipping point yet where we go beyond the adaptive capacity of human civilization or beyond the adaptive capacity of living things. I don't think we've yet crossed that line. We have certainly committed to some dangerous changes in climate already and it's possible we have already warmed the oceans enough that they're going to melt the ice shelves around Antarctica enough to destabilize enough of that antarctic ice to give us ten feet or eleven feet of sea level rise by the end of the century. That is a very real possibility.

And so there is some amount of adaptation that we are going to have to engage in. It isn't just a choice between mitigation - reducing our carbon emissions - and adaptation - taking measures to deal with the changes that are coming. We're going to have to do both. But I think a sober look at what the science has to say, based for example on the most recently released report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change just a year or so ago. The best available science tells us it's not too late but there is an urgency unlike anything we've seen before. There is an urgency now to reduce our carbon emissions or we will potentially cross into what can only be described as the danger zone.

Thom Hartmann: How long before we might hit that danger zone? You wrote a piece for Scientific American

suggesting just 2036 as I recall.

Michael Mann: Yeah. If we continue with business as usual, our carbon, burning of fossil fuels, with the growth of emissions in countries like China, India and South America, it's only a matter of a couple of decades before we cross that two degree Celsius warming and the science tells us a lot of bad things will happen with two degrees Celsius warming of the planet, but even worse things will happen with three degrees Celsius warming and far worse things with five degrees Celsius warming. And we are on track to exceed five degrees Celsius warming of the planet by the end of the century if we continue with business as usual. That's a larger change in global temperature than from the height of the last ice age when ice sheets covered New York to today.

We are talking abut a monumental change in climate on a time frame far shorter than anything that nature has ever produced before, and that's the real problem. We're talking about rates of change, magnitudes of change and rates of change that have no precedent in the past and may indeed, as some have speculated, lead to the sixth great extinction event. We are on course to the sixth great extinction event if we don't change our way of doing things.

Thom Hartmann: More with Michael Mann right after the break.

Thom Hartmann: Welcome back. I'm talking about climate change and the cult of climate denial with one of the world's leading climate scientists, Dr. Michael Mann, distinguished professor of meteorology and director of the Earth System Science Center at Penn State University, and author of the book The Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars: Dispatches from the Front Lines.

Dr. Mann, one of the things that concerns many scientists is the large stores of methane under the Arctic permafrost and under the Arctic Sea. There's actually more carbon apparently there under the surface of the Arctic than there is in the Earth's atmosphere. What happens if that carbon gets out and how could that happen?

Michael Mann: Yes, there was a study just last year that suggested that we could essentially double the warming from CO2 alone, from carbon dioxide alone, from the potential release of some of this methane that's trapped in permafrost, that's trapped in the coastal shelves of the Arctic Ocean. And we can't rule out that scenario. It's a reminder that there is uncertainty. There are uncertainties, there are potential surprises that loom and they're not going to be pleasant surprises.

There are potential aggravating factors like the potential destabilization and release of methane that could make the problem worse than we currently project with our climate models. And so it once again highlights the fact that in many respects climate scientists have been overly conservative in the scenarios that we've envisioned and the changes that we've projected for the future. It could potentially be a whole lot worse. Now, there's a lot of uncertainty there and there is a fierce debate within carbon cycle scientists over just how much of that methane is potentially releasable into the atmosphere with the warming projected over the next century.

Some scientists say that only a fairly small part of that is mobile, can be mobilized by global warming, but some scientists think that potentially a much larger amount of that methane could be released. To the extent that there is uncertainty, it could once again break, not in our favor, but against us. And so, it's once again reason for precaution for not tampering any further with a system that we don't understand perfectly. And that's what we're doing. The distinguished climate scientist Wally Broecker of Columbia University once said it is like we are poking an angry beast with sticks. That's a dangerous thing to do, and that's what we're doing.

Thom Hartmann: This is the first time in this hour that we've mentioned methane. Can you just very quickly for viewers who might not understand why we suddenly went from talking about carbon dioxide to methane, what's the difference between carbon dioxide and methane and why should we be concerned about methane in the Arctic or anywhere else?

Michael Mann: Yes, methane, it turns out, is a more potent greenhouse gas than CO2. A single methane molecule absorbs more atmospheric heating than a single CO2 molecule. Now, there are other complications in comparing them, because methane has a different lifetime in the atmosphere. CO2 stays around for a very long time . Methane tends to be absorbed by the climate system on a time frame of a decade or two decades and because of that it just doesn't stick around as much. And so when you are comparing the two problems you have to look at not just how much warming you can get, but the time scale over which that warming is likely to happen.

And it turns out that your metric of danger; what you think of and what you envision as dangerous climate change is going to determine to some extent the relative risks of these two contributors. If you are worried that we are going to pass some sort of tipping point within the next decade or two decades, where we trigger things like the dramatic acceleration of the melting of the ice sheets or the shutdown of the ocean circulation pattern that helps warm Europe, the conveyor belt ocean circulation, or a fundamental shift in the way that El Niño behaves that could have profound impacts for drought and rainfall patterns around the world, if you're worried abut those sorts of dramatic changes that could be triggered by an abrupt short term amount of warming, then methane, it turns out, is a real player. Methane really has the potential to aggravate the warming that we see over the next decade or two.

Now if your worried about sort of the longer term warming of the planet, the longer term changes in climate, well then it's really CO2 which is the main player. And so, to some extent, one's concern abut CO2 versus methane is going to depend on the things you're concerned about happening. What your tolerance is, what your metric is for defining dangerous changes in climate.

One would be best served by avoiding the increase in concentrations of both of them because they carry different types of risk as far as climate responses are concerned.

Now, methane is getting into the atmosphere a number of different ways. Methane is produced by livestock and by agriculture, so there's a certain amount of human-produced methane from agricultural practices, from livestock raising, but it's also escaping into the atmosphere because of fracking, because of natural gas drilling, the use of so-called fracking - hydraulic fracturing - to try to get at the methane, the natural gas that's contained in the bedrock below, where fluids are injected and they crack the bedrock and allow that

methane

to escape and potentially be recovered. But some of it actually escapes into the atmosphere. It's what we call fugitive methane.

And so the process of natural gas extraction and fracking, that's potentially introducing methane into the atmosphere. We don't know exactly how much. It could potentially offset the nominal gains from natural gas which is just a little less intensive from the greenhouse warming standpoint as burning coal. It doesn't produce quite as much CO2 for the amount of energy that's generated. So some people have said well it's a natural gas, if we switch to natural gas from coal that can help lower our carbon emissions. But if a lot of that natural gas is actually escaping into the atmosphere, and

that natural gas is mostly methane which is a very potent greenhouse gas, it could actually be making the problem even worse.

Then there is the natural gas, rather than methane, that is certainly trapped within the climate system, frozen in what is known as clathrate crystalline structure along the continental shelves of the oceans, the methane that is trapped in the permafrost. If we warm the planet up enough, we could, as we were discussing earlier, potentially release a lot of that, mobilize a lot of that methane and that again would add substantially to greenhouse warming.

So, it's a potentially important player and we have to be thinking not just about CO2, but about other greenhouse gases that are being produced by human activity like methane.

Thom Hartmann: Moving on to climate denialism; how has this taken such a grip in America? Is it as prevalent in the rest of the world?

Michael Mann: Well, climate denialism to some extent has been manufactured. There is an ongoing decades-old industry-funded disinformation campaign to confuse the public about the science of climate change. So fossil fuel interests, and their abettors the Koch brothers, Koch Industries, other conservative interest groups have been spending tens of millions of dollars to pollute the larger public discourse over this issue by manufacturing controversy, by misrepresenting the science, by attacking the science and scientists in op-eds and through conservative media outlets that have distorted the science of climate change for their viewers. Fox News, the Wall Street Journal editorial pages, which is a fount of misinformation and disinformation when it comes to climate change.

So that didn't just happen by accident. It happened because there was a well laid out well-financed strategy detailed decades ago to generate a fake debate about climate change to prevent action from occurring. To prevent the regulation of carbon emissions. Because those vested interests well knew that as long as they could maintain the appearance of controversy, the appearance that climate change is still debated by scientists, that would be enough to convince the public that we're not yet, that we don't have the degree of certainty necessary to act on this problem when ironically, if anything the uncertainty is breaking in the other direction. Things are potentially going to be even worse than what we have projected previously.

So, there has literally been this poisoning of the public discourse through tens of millions of dollars of special interest funding, of front groups. They hire fake experts with impressive credentials to attack their fellow scientists, to attack the science. They have created front groups which manufacture misinformation, which produce talking heads that go on television news programs, that write op-eds in leading newspapers, misleading the public about climate change. You see it here in the U.S. where there's a lot of fossil fuel money and there's a very large and powerful fossil fuel industry. You see it in Australia. You see it anywhere where there is a large vested interest that doesn't want to see the regulation of carbon emissions. You see these sorts of misinformation campaigns intended to distract the public and policymakers and lead them astray and prevent action from being taken.

Thom Hartmann: Well, and meanwhile, we see that, at least with television, for example, there's actually very little coverage of climate change. PBS beats CBS, ABC and NBC by almost 2 to 1 or maybe more than 2 to 1 last year in just even discussing the topics. Why do you think it is that Americans are so willing to accept that narrative of the climate deniers? Is it because there's so little coverage or is it because people just want a rosy outlook?

Michael Mann: Yeah, I mean, I think it's a combination of factors. The fact is that many of these television news programs and many of the networks receive a lot of advertising money from fossil fuel interests. You can't watch any of the cable news networks without seeing multiple advertisements from the American Petroleum Institute, from ExxonMobil, sort of greenwash, where they present themselves as caring about the environment at the same time they are spending tens of millions of dollars sort of in misinformation, in perpetuating misinformation about climate change. The same time that they're hiring front groups to attack the science of climate change, sort of speaking out of both sides of their mouth. And so I think to some extent it has to do with biting the hand that feeds you. Many of these networks probably don't want to upset these corporate sponsors.

And so there hasn't been the sort of hard-hitting journalism, whether it's in the newspapers or whether it's on television, that there ought to be given the magnitude of the problem and the magnitude of the threat that it represents.

Thom Hartmann: Right. More with Dr. Michael Mann right after this break.

Welcome back. I'm talking about the future of our warming world with one of the world's leading climate scientists, Dr. Michael Mann, distinguished professor of meteorology and director of the Earth System Science Center at Penn State University, and author of the book The Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars: Dispatches from the Front Lines.

Dr. Mann, we've put off dealing with this issue in any serious way for about 30 years that it's been fairly irrefutable. What needs to happen now to curb the worst outcome of climate change?

Michael Mann: Yeah, well as you say, we have unfortunately procrastinated in acting on this problem and there's a great procrastination penalty. If we had acted on the problem decades ago, when we had enough information already to know that climate change was real, that it was caused by human activity, that was going to increasingly be a threat, if we had acted then, then we would have been able to undergo a fairly slow and methodical transition away from fossil fuels towards renewable energy, to other forms of energy.

We could have undergone a slow enough transition that it could be accomplished fairly inexpensively. If you like, think of it, if you think of the carbon emissions, if we had brought them to a peak decades ago and had then gently brought them down in such a way as to avoid dangerous warming of the climate, the emissions curve would have looked like a bunny slope. Think of it as a bunny slope, OK.

Instead, by having delayed action, the peak is now much higher and we have to bring it down far more dramatically and far more quickly. So we've gone from the bunny slopes to the double diamond, the black double diamond slopes. That's the cost of not having acted on this problem sooner. And of course there's all the damage that has been done by climate change in the meantime.

So there has been a huge procrastination penalty in not have acting when we had enough information to act. That having been said, there is still time to act so that we avert the worst potential consequences of climate change. When we talked about the two degrees Celsius warming, three and a half degrees Fahrenheit warming, as being a warming threshold that we definitely want to avoid, beyond which we really start to see some of the bad things happen, we can still avoid crossing that two degree warming threshold, but it's going to take concerted action.

And what it's going to mean is that we have to very rapidly transition away from our current reliance on fossil fuels; on coal, on oil, on natural gas, and move towards solar energy, renewable energy, wind energy. We have the technology. The irony is that we don't have to invent new technologies to solve this problem. The technology already exists. We just have to scale it up.

And there is peer-reviewed work, some excellent work done by folks at Stanford University, Mark Jacobson and his group at Stanford University, that have shown that we have the technology, we have the ability to wean ourselves from fossil fuels by mid century, almost completely by mid century. And we have the ability to scale up solar and wind and other renewable sources of energy and they're doing it. It isn't just theoretical.

Germany is doing it. Germany is now meeting 30% of its energy demand from renewable energy alone.

We are seeing dramatic gains made to the point where for the first time in many decades last year we saw global economic growth without a growth in carbon emissions. There is now what appears to be taking place a decoupling of our economy from fossil fuels. We're starting to turn the corner but we have to turn that corner even faster. We really have to dramatically incentivize the shift away from fossil fuels. We've got to stop burning dirty coal. We've got to massively deploy renewable energy if we are going to avoid crossing those dangerous thresholds.

Thom Hartmann:

You talked about, you kind of glanced off the economics of this. Let's talk about that. Fossil fuels receive massive subsidies world-wide, from the actual subsidies to fossil fuels, to subsidies like, you know, the American navy protecting our shipping lanes to get Saudi oil here. But renewables produce energy more cheaply when you consider those extra costs, and that's not even costing the externalities which I'd like you to address also. So what will it take to make the economics favorable for renewable energy to quickly overtake fossil fuels as a principle energy source around the world?

Michael Mann: Yeah, that's exactly right, and what we're seeing amazingly is that renewable energy is already making significant inroads in our energy economy even without those incentives. Imagine what we could be accomplishing right now if we put the proper incentives in place. Because right now we have an unequal playing field in the global energy market. We are, as you allude to, providing huge subsidies and incentives to the very form of energy, fossil fuel energy, which is destroying our climate; destroying, in some sense, our planet, and not providing similar incentives for the forms of energy, renewable energy, that can help us wean ourselves off of this dirty, dangerous fossil fuel energy.

So, the incentive structure right now is completely inverted from what it needs to be. I'm one of those people who thinks that the market can solve this problem. We can solve this problem in a market economy, through market mechanisms, but the playing field has to be leveled. And right now it's not level because we're providing incentives to the energy sources that are hurting the planet and not providing equal incentives to the energy sources that can help save the planet.

Now I saw just the other day that one of the Republican candidates for president Jeb Bush actually stated publicly that he thinks that we should do away with fossil fuel subsidies. And he was half right because he also said that we should do away with subsidies for renewable energy. And that's wrong. What we need to do is do away with the incentives for fossil fuel energy and incentivize the clean energy sources that can help us avert this potential catastrophe.

Thom Hartmann: Yeah, in fact, my understanding is that from news reports that the world wide subsidies for fossil fuels right now are around 5 trillion dollars a year. That would buy a lot of renewables.

At this point will we even know when we're seeing the worst outcomes or has erratic weather simply become the new normal?

Michael Mann: Yeah, the problem here is the variable tip of the iceberg, right. By the time you see the tip of the iceberg, it's too late. The Titanic learned that the hard way. And so it is with climate change. By the time you are able to see in the day to day weather, in the sorts of extremes that in daily weather, by the time the signal is so large that we are literally seeing it in the day to day weather, well then you know that we've gone too far already. You know that there's much more in the pipeline.

Because it is, to go back to that analogy, like the Titanic. The climate is this huge ship. It has huge amounts of inertia, what we call thermal inertia. The oceans can absorb a very large amount of heat so the climate system warms up fairly slowly, it's burying some of that heat below the surface. That's contributing towards global sea level rise, so it is this slow but steady warming that will persist for decades.

And in fact if we stopped burning carbon right now, not only would the surface of the Earth continue to warm for half a century, probably give us at least another half a degrees Celsius, but the oceans would continue to warm for centuries, and sea level rise will continue to rise for centuries.

So, what that tells us is that we have already committed to a certain amount of additional and potentially dangerous changes in climate. We are going to need to adapt to those changes that are already locked in. There's a certain amount that's baked in, there's a certain amount of additional climate change that's baked in, that we are going to need to deal with, that we're going to need to find ways to adapt to the negative impacts of those climate changes that are already locked in. But we can still avoid the vast majority of climate change if we act now, the most dangerous and potentially irreversible changes in climate if we act now.

Thom Hartmann: This summer the Pope convened mayors from around the world to address what cities can do at the local level and small scale renewable energy is being deployed much more rapidly than large scale installations, at least from some reports I've seen. Is this how we have to address climate change, a grass roots bottom up approach?

Michael Mann: Yeah, and we see evidence of that here in the U.S. Right now we have, there's obviously intransigence in the U.S. Congress when it comes to passing meaningful comprehensive climate and energy legislation. We're just not going to see that as long as the politicians who were put in place by the Koch brothers in the last election through massive funding to put in place politicians who would be sympathetic to their agenda of climate change inaction.

Obviously they now have a stranglehold on the U.S. House of Representatives and to some extent on the U.S. Senate as well. So in the absence of the potential for congressional legislation, what we need and are seeing is action at the Executive level. President Obama has pretty much done everything within his power to impose new carbon emissions limits on coal-fired power plants, increased fuel efficiency standards again through the EPA.

You see states banding together. And my friend Jerry Brown, the governor of California, is taking a lead role in seeing that California is at the leading edge of introducing a cost of carbon in their state economy so that carbon emissions are now going to be priced, again to start to internalize the damages done by the emission of carbon into the atmosphere.

And California is banding together with Oregon, Washington, and even British Columbia to institute a regional carbon emissions consortium. The northeastern states are doing something through what's known as

RGGI, another regional carbon permit consortium are doing something as well.

You see mayors passing measures at the local level, at the city level to do something about carbon emissions. The mayor of Los Angeles for example is leading that effort. Philadelphia, the mayor of Philadelphia, Michael Nutter, as well, as part of that effort among mayors of the major cities to do something to act on this problem in the absence of congressional leadership.

And of course there was this very critical agreement that the president struck with China within the last year to make sure that the two largest nations, the two largest emitters of carbon on the face of the planet are engaged in efforts to bring down their carbon emissions.

Thom Hartmann: Dr. Michael Mann, it has been a pleasure and an honor talking to you. Thanks so much for being with us tonight.

Michael Mann: Thank you, it's been a pleasure to talk with you as well.

Thom Hartmann: And that's The Big Picture tonight. Don't forget, democracy begins with you. Get out there. Get active. Tag, you're it!

Transcribed by Sue Nethercott.